Op Eds & Articles

The east-central Chinese city of Kaifeng — one of the seven ancient capitals of China — has two claims to fame: First, during the Middle Ages, it was considered the world’s largest metropolis, with an estimated 1.5 million inhabitants, and secondly, it’s the focal point of China’s contribution to Jewish history.

Today, Kaifeng is home to around 800,000 people — yet only 500 of those 800,000 claim Jewish ancestry. Shi Lei, a 31-year-old representative of that tiny community, spoke with the Israel-Asia Center during an interview in Silver Spring, Maryland. That was one of the many stops on a three-week North American tour sponsored by the Jewish organization Kulanu, based in New York, with cooperation from the Sino-Judaic Institute in Seattle.

Here are excerpts from our interview:

Q: What is the objective of your current visit to the United States?

I don’t think lots of American Jews know that in Kaifeng, China, there are Jews like me. So I want to raise awareness and get donations to support the community, which we will use for people’s education. Kaifeng is a relatively poor city in China, and we need donations — especially in the future, if more people go to Israel to study.

Q: How did you learn to speak Hebrew so well?

I was the first Kaifeng Jew ever sent to study Judaism in Israel. In 2001, Rabbi Marvin Tokayer [of New York] arranged for me to enroll in a one-year Jewish studies program at Bar-Ilan University. After that, I went on to study at Yeshiva Machon Meir [in Jerusalem].

Q: How did average Israelis react to meeting a Chinese Jew?

The Israelis were friendly, but when I was studying there, I was always in an Orthodox environment. Normal [secular] Israelis were a little surprised at the beginning to meet me. But I could tell that they didn’t care, because in Israel, almost everyone is Jewish.

Q: Did anyone in Israel question your Judaism?

In Israel, to tell you the truth, they don’t recognize Kaifeng Jews as Jewish, according to Halacha. My first day at Bar-Ilan, one guy came up to me and said, ‘You say you’re a Chinese Jew. Is your mother Jewish?’ I said no, and he replied, ‘so you’re not Jewish.’ It was like a cup of cold water had been poured on my head.

But since the rabbi had given me a chance to study Judaism, I thought it was more important to sit down and learn something instead of arguing with this guy.

Q: Why did you to go back to China rather than stay in Israel?

Because I am the first from my community. That’s why I decided to come back to Kaifeng to share what I learned with my friends. Since I’ve gone back to China, 16 other young people from Kaifeng were sent to Israel to study Judaism. Eight of them have already made aliyah.

Q: How did Jews come to live in Kaifeng, so remote from other centers of Jewish life?

Kaifeng’s Jewish ancestors came from Persia, where they were persecuted. In ancient China, being an official meant everything — wealth, power, influence. Every person enjoyed the same rights, and even a Jew was allowed to become an official. This was considered the best way to become successful in China.

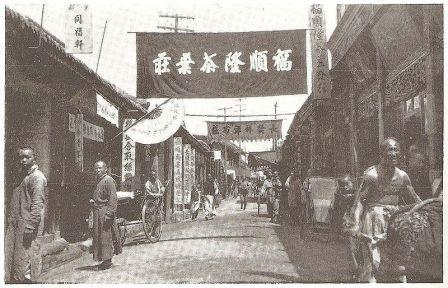

Eventually, the Jews were able to buy a large piece of land in downtown Kaifeng. You can imagine how rich and successful they were. They lived on two streets: South Teaching Torah Lane and North Teaching Torah Lane. In the 14th century, we reached our peak of around 4,000 Jews. Most of those who came from Persia were men, so eventually they married local Chinese women. Those ladies had to go through kosher conversions.

Q: What happened to the community?

Things started declining in 1810, when the last rabbi died. Because few people could read Hebrew — and because the Torah had not been translated into Chinese — the community gradually withered away.

Around the 1850s, the last synagogue in Kaifeng fell into ruin. The Jews had by then become so assimilated into Chinese culture that they were ignorant of Torah and their traditions. It was useless to renovate the synagogue again.

By the early 20th century, the community was so poor that the Jews even sold 10 of the Torah scrolls to Western missionaries. So today in Kaifeng, not only there’s no synagogue, but no Torah scrolls either.

Q: Your family recently set up a “mini-Jewish museum” in Kaifeng. What is the purpose of this project?

Many tourists and scholars coming to Kaifeng wanted to see something tangible about the Jewish community. But there wasn’t anything tangible to see. Today, there is. People [visiting our museum] can see many historical pictures of the Kaifeng Jews, and also Jewish artifacts. This museum is very small, but we hope to expand it.

Q: Has China’s economic success had much impact on the Jews of Kaifeng?

Yes, they’ve benefited from it, because as China becomes prosperous so do we.

Q: How do you celebrate Shabbat?

We do a simple Shabbat dinner in my family’s mini-Jewish museum. We light candles, we share a meal. It’s not like 25 years ago, when Jewish families didn’t know each other. Nowadays, we stay in touch. Sometimes we get 40 or 50 people to a Shabbat dinner. Our classroom — where I volunteer to teach when I have time — is also our community center where we meet for festivals.

Q: Does anybody keep kosher in Kaifeng?

We are able to get kosher food from the Chabad in either Beijing or Shanghai, but so far we don’t because it costs a lot of money. Also it’s complicated to transport by train or plane. I cannot really live a kosher Jewish life, and I cannot keep Shabbat because sometimes when Jewish tourists come, I have to lead tours.

Q: How does the fact that Judaism is not a recognized religion in China affect the Jews of Kaifeng, if at all?

In China, there are criteria for recognizing different religions. A group of people must still practice their own religion. They must still stay in their own area, and must speak their own language. So if these people meet the requirements, they can be considered. Nowadays, we are learning Hebrew, but we don’t actually practice. We’re in the learning process.

Even so, within the limits of Chinese law, we can do a lot of things. Teaching Hebrew or how to celebrate Jewish festivals doesn’t cause any problems. But we must think of a way to help the community continue.

Back

Back