Op Eds & Articles

Aiman Zarul previously worked in the political section at the Delegation of the European Union to Malaysia, and is presently the Political and Economic Affairs Officer at an embassy in Kuala Lumpur. He is a founder of the Caucus for the Improvement of Malaysia-Israel Relations that advocates culturo-religious cooperation between Muslims and Jews through Malaysia-Israel engagement in economics, politics and social interaction.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect those of the Israel-Asia Center.

Read Aiman Zarul’s previous article in this series

Sometime in 2009, while touring the aisles at my local Kuala Lumpur supermarket, I came across an incongruous item: metal nut-crackers, encased in fetching blue packages bearing Hebrew inscriptions. Loosely deciphering several references including ‘Tel Aviv’, I jovially interrogated my bemused cashier about the origin of the stock, in the process apprising her of its country of manufacture. It was the first time I had seen Israeli products stocked in Malaysia, and it was also to be my last: returning to the store two weeks later, I found that the Israeli nut-crackers had been replaced with harmless Japanese can openers.

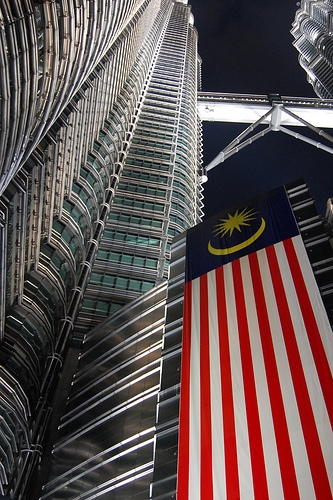

My experience was a practical lesson in the blurry enterprise that is Malaysia-Israel trade. Malaysia and Israel do not share political relations, and since 1965, bilateral trade has been indirectly channeled through third markets in a largely discreet process that is consistently disavowed by the Malaysian government. A legacy of popular anti-Israelism and staunch pro-Palestinian sentiment further complicates the picture. Hence why Malaysia’s former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed took a slightly harsher lesson in January this year when he accused opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim of surreptitiously disseminating Mossad-supplied data on Malaysia-Israel trade during the former’s tenure. Instead, Mahathir was widely seen as affirming past trade with Israel, and was thus rebuked by conservative Muslim Malaysians for having countenanced such trade. What we both learnt from our separate experiences was that in Malaysia, Israel is still very much taboo.

This is counter-intuitive. Mahathir’s replacement by the milder Ahmad Badawi in 2003, followed by Badawi’s own departure in favor of the Western-educated and secular economist Najib Razak in 2009, would have flushed out much of the virulent anti-Israel sentiment that typified Mahathir’s 23-year rule. Alongside rising income levels, Malaysian civil society has also strengthened in recent years (28 April saw a large pro-democracy rally in Kuala Lumpur, the second in two years), its advocates bidding to reconcile Malaysia’s state-enforced Islamic-Confucian social codes with socially progressive norms such as secularity and pluralism. Combined, these dynamics ought to have erased anachronistic preconceptions that hinder the sort of pragmatic thinking that Malaysia’s sustained growth needs. But at least in the context of Israel, they haven’t. Public figures still shy from suggesting trade with Israel for fear of receiving the same rapping as Mahathir and Anwar, leaving the private sector to take the lead.

But the hurdles that private actors face are impressive if not prohibitive. Malaysian and Israeli imports are subject to a double layer of import/export licensing rules. On the Malaysian side, this is a progression from the outright ban on Israeli imports (and exports to Israel) that operated before 1998, but the current rules are opaque and highly discretionary. While Israeli companies are able to indirectly flex into the Malaysian market from Singapore-based offices, the rules are a disincentive for Malaysian companies interested in tapping into opportunities in Israel. Ironically, this means that only Malaysian state bodies have the latitude and bureaucratic savvy to engage Israeli entities, and since Mahathir’s departure there have indeed been a handful of instances of Malaysian state-linked firms subtly transacting with Israeli businesses, particularly in confidential or security-related goods and services.

Today, the landscape is less discernible. Three years into his premiership, Najib has kept silent on Israel. He has continued Mahathir’s vision of turning Malaysia into the global hub for Islamic finance, but despite his moderate outlook and efforts to distance himself from Mahathir’s more controversial rhetoric, his job of strengthening ties with other Islamic economies (and re-forging ties with post-Arab Spring governments, many which are controlled by parties openly hostile toward Israel) in the fulfillment of this vision may in fact make it more difficult to ease trade channels with Israel. To be sure, Najib has worked to reinvigorate Malaysia’s traditionally tight relationships with Western partners, long neglected by his predecessors in favor of closer ties with the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) and non-aligned states. Under him, Malaysia has also halted petroleum and palm oil exports to Iran in compliance with U.N. sanctions. But if these steps suggest that a softer stance towards Israel is inevitable, then a latent cautiousness caused by Najib’s own shaky standing among the young conservative rungs of his UMNO party and amplified by the imminence of his first general election, could very well disappoint.

So where are we going? Amongst Malaysia’s small but expanding foreign-educated youth, resolute apathy towards Israel is gently giving way to guarded curiosity. There is a growing interest among high-tech startups (many owned by recently returned graduates) in Israeli technology and business concepts. According to The Economist, Malaysians form a substantial proportion of Muslims taking advantage of current peaceful conditions to join special pilgrimage tours to Jerusalem, and as demand for tour places surges, so is the number of travel agencies approved by the Malaysian authorities to operate such tours. In the formal economy, trade data collated by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization suggests that much of Israel’s bourgeoning palm oil imports are in fact re-sales of Malaysian produce (Malaysia produces 51% and exports 62% of the world’s palm oil). While a host of factors has caused indirect material trade between Malaysia and Israel to flag considerably over the last 15 years, the substitution of trade in tangible goods for a trade in experiences and ideas may in fact augur very well, if not better, for the Malaysia-Israel relationship.

Back

Back